DIY Analogue XLR Interconnects Recipe

The XLR connector was invented by James H. Cannon, founder of Cannon Electric in Los Angeles, California (now part of ITT Corporation), and for this reason it was sometimes colloquially known as a Cannon plug or Cannon connector and in Japan as Cannon jack, though this term has since fallen out of common usage in the industry.

Analogue balanced interconnects, also known as XLR interconnects or cables, primarily used with professional audio, video, and stage lighting equipment. The XLR connectors are circular in design and have between 3 and 7 pins. They are most commonly associated with balanced audio interconnection, including AES3 digital audio, but are also used for lighting control, low-voltage power supplies, and other applications. XLR connectors are available from a number of manufacturers and are covered by an international standard for dimensions, IEC 61076-2-103. They are superficially similar to the older and smaller DIN connector range, but are not physically compatible with them. If you want to install custom audio systems in your home, DIY (Do-It-Yourself) XLR cables ensures that you have a clean system with no excess cable. Here’s an easy DIY analogue XLR interconnects recipe:

Materials

- Set of 02 XLR Male plugs and 02 XLR Female plugs as this recipe is for a stereo connection

- Two sets of multi-conductor cables of equal length

- Wire cutter

- Wire stripper

- Helping hands with alligator clips or tweezers

- Table-top or suction base vise

- Solder

- Soldering iron with a minimum of 25 watts and a narrow conical tip

- Heat shrink in 02 different colors and sizes (optional)

- Heat gun (optional)

- Cable tester or a digital multimeter

Method

Turn on the soldering iron.

- Do this first so it is hot enough when you begin soldering.

- Make sure the tip of the iron is placed inside the soldering iron stand, and that it is safely out of the way so you do not accidentally bump into it.

Cut the audio cables to the length that you need. For this recipe we will consider the cables as having 04 individually insulated conductors – 02 for ground (pin-1), 01 for hot (pin-2) and 01 for cold (pin-3) pins.

- Choose a length that is appropriate for the application. Recommended length is ideally between 0.5m to 10m.

Remove or strip 1/8 inch (4 mm) of the individual jacket around the conductor wires.

- If the cable is too big to fit in one of the gauge holes on a wire cutter, use the sharp edge at the base of the wire cutters.

- Apply light pressure with the cutting tool and spin the cable around until you cut all the way through the outer jacket. Be careful to avoid cutting the conductor wires.

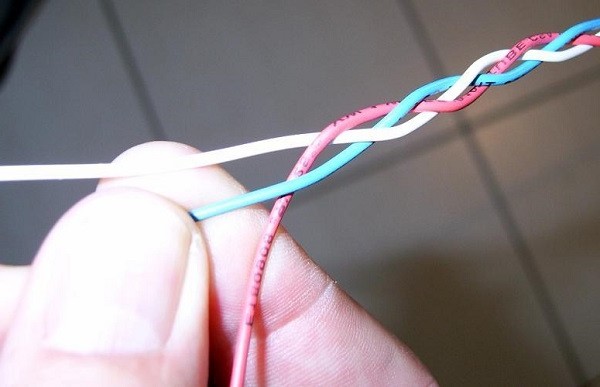

- Cables may have between 3 to 16 conductors. If the conductors are in multiples of 03 then braiding the common colors together is another effective way of managing the cables.

- Coat or tin the conductor ends. Applying a small amount of solder to the twisted ends keeps them together and it will be easier to connect them to the XLR end.

- Heat up the wire and hold the solder on the opposite side of the iron touching the wire. The heated conductor wire should be hot enough for the solder to melt and apply an even coat on the exposed conductor tips.

Use heat shrink (optional).

- Cut a medium diameter heat shrink tube about 1 inch (2.5 cm) long. Slide the heat shrink over the conductor wires onto the cable itself. You will need this only if there no chuck inside the XLR plug.

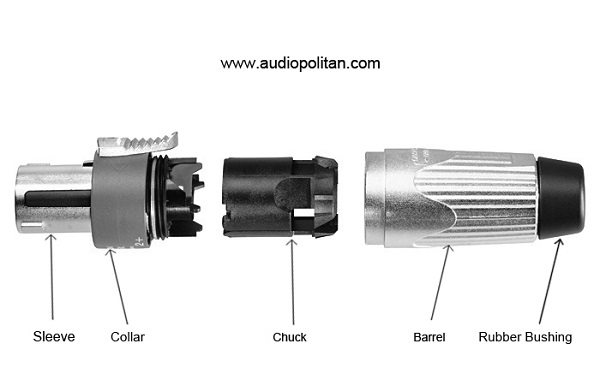

Disassemble your XLR plugs and keep all components neatly in one place.

- Being organized and methodical goes a long way in DIY cable making.

Slide the outer barrel of the XLR end onto the cable past the conductor wires.

- This is necessary in order to be able to screw the barrel back once you’ve soldered the conductors to the XLR plugs.

Solder the conductors to the XLR Male end.

- Place the Male XLR plug’s collar in-between the jaws of the table-top vise and lock it in place.

- Align the stripped cable in line with the rear side of the XLR plug’s collar using the helping hand as shown in the picture below.

- If the individual insulation of the conductors are not color coded then use a removable tape to mark them individually for easy identification. Remove the tapes once the conductors are soldered to their respective pins.

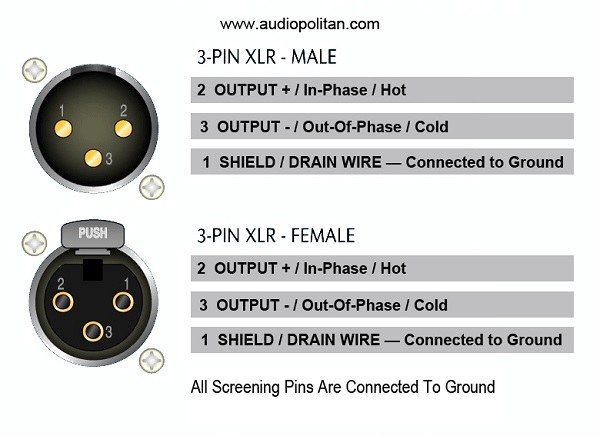

- Find the 03 U-shaped solder cups that runs in line with Pins 1, 2 and 3 as shown in the picture above. Insert the tinned conductor ends, marked for their respective pins, into their respective solder cups and apply the soldering iron to the tip of the exposed conductors, one at a time. Apply just enough solder that can hold the conductors to their respective pins – no less, no more!

Solder the conductors to the XLR Female end.

- Repeat the same steps as mentioned above for the Male XLR plug.

- Position the chuck to hold the 04 individual wires firmly to aid flexibility and strength.

- If there is no chuck then pull back the medium diameter heat shrink over the soldered pins and shrink them using a heat gun for added rigidity and strength.

Thread the outer barrel and the head (collar) of the XLR plug together.

Repeat the above steps for the remaining 02 XLR plugs.

Test the cables for continuity and correct polarity using a cable tester or a digital multimeter.

Apply large diameter heat shrink, specifically designed for XLR plugs, partially over the XLR barrel and the cable using a heat gun for added appearance and rigidity (optional).

- If you plan on making multiple XLR cables for 5.1 or 7.1 application then use different colored heat shrinks for easy identification.

Tips

If possible, use a high-quality soldering iron. A good soldering iron heats up to a higher temperature than the lower-quality models. The process will be easier and the results will be much cleaner.

Most XLR Male and Female plugs will have their pins and solder cups marked as 1, 2 or 3 to avoid confusion. Some XLR plugs may not have their pins and solder cups marked as 1, 2 and 3. You may use the XLR pin configuration shown above as a reference.

Some XLR plugs may not have chucks inside them to hold or lock the ground, hot and cold conductors firmly in place. Applying a heat shrink in this case is a quick fix that ensures a robust and flexible connection. The Cannon plugs, are an exception, they do not have a chuck; it comes with a hollow rubber bushing and there are two tiny screws on either side of the barrel to squeeze the bushing that helps to hold the cables tight. Though the Cannon plug look like any XLR plug they are actually 02 halves of a barrel held together by 03 screws.

Controversies

There are some controversies that every DIY audiophile and cable manufacturer is bound to face it at some point or the other. They make for some really interesting read. Here are the most popular ones:

Dielectric material: The type of dielectric material used affects the quality of sound. The lower the dielectric constant the better the sound quality.

Heat shrink: When used to add rigidity to the cable clamp could affect the quality of sound due to the change in the dielectric constant.

XLR plugs: Available in brass, copper and silver that are plated with noble metals to avoid corrosion. There is a school of thought that believes that the material used does not matter as long as the XLR plugs are well designed and made.

Conductors: Available as solid core or stranded ranging from 30 AWG (American Wire Gauge) to 22 AWG in 02 to 16 conductor / strand designs for making analogue interconnects. They are also available in copper and silver in various purity ratings. Copper is claimed to have a warm sound, whereas, silver is claimed to have a well-lit presentation. There is a school of thought that believes that a cable of sufficient gauge, regardless of the type of metal used, should not make any audible difference at all.

Shielding: A tubular copper or aluminium braid / foil which covers the entire length of the cable bundle is the standard. It’s suggested that most A/V playback systems may not need shielded RCA cables if the lengths are kept reasonably short. In some environment, unshielded RCA cables may introduce audible hum due to EMI (Electromagnetic Interference) / RFI (Radio-Frequency Interference) from adjacent electronic equipment or mobile phones.

Braiding: When 03 or more conductors are used braiding helps in cable management and appearance. Some claim that braiding also acts as a shield against EMI / RFI.

Wrap-up

Every cable design is subject to some kind of a compromise; it’s a balance between performance and penalties. This DIY analogue XLR interconnects recipe is just one way to skin a cat. This post is likely to be updated time and again with either relevant points or photographs.

Experienced DIY enthusiasts may have an advantage due to their thorough understanding of metallurgy, quality of materials used, cable geometry and of course craftsmanship that comes only with practice. If you have limited soldering experience, ask a DIY specialist to do the job for you.

DIY opens up to a world of endless possibilities for every audiophile. Apart from understanding and eliminating bottle-necks that improves A/V playback performance, it is also a very creative process.

If you want us to build this cable for you then kindly contact us and we are more than happy to assist you.