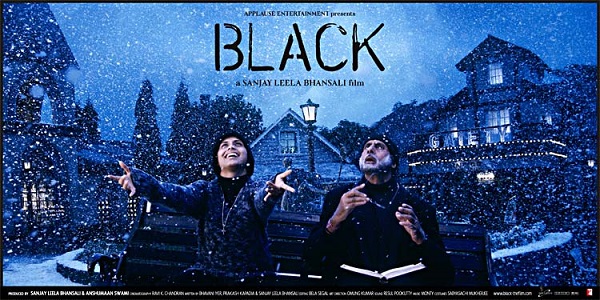

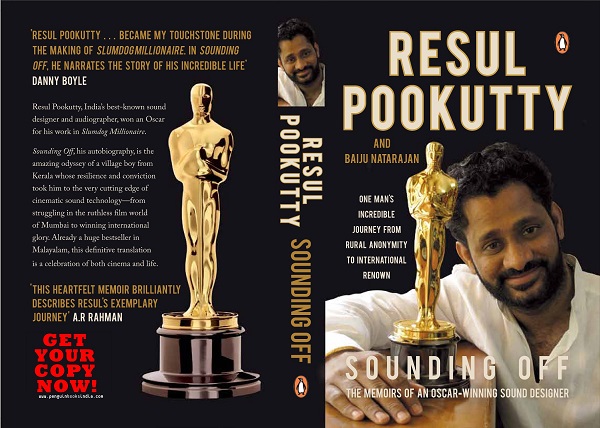

Interview With Resul Pookutty

Resul Pookutty is the man behind Canaries Post Sound. He is India’s best-known sound designer and audiographer. He engineered the sound for the movie—Slumdog Millionaire that won him an Academy Award in 2009.

GD: What does music mean to you?

RP: To me it’s an expression of my feelings. I get moved when I listen to music. I get to know something that is beyond me in music. There exists something which helps to connect with oneself, that’s music to me. I have heard a lot of music. I’m not a musician myself. I craved to learn music, when I was a kid, but my opportunities at home where not good enough for me to learn music. I remember the place where I was born and brought up, there was a place called Ajanta Academy. I remember while I walked past Ajanta Academy, when I heard the sounds of the Tablas, Veenas and Tanpuras, my soul used to get attracted to that place. I stood outside Ajanta Academy and listened to music. I did not have the means to study music because everything outside of my schooling was a luxury and we could not afford that. So it always remained with me like a thorn, something that pricks me every time.

I started listening to music, very seriously, when I came to the Film Institute. My father was a lover of classical music so he used to listen to music on the radio. He used to listen to the classical kacheries (Carnatic music concerts) at night and my mother hated it. The nearest temple was our only source of entertainment or the occasional circus that used to come to our village. Every festivity at the temple used to include either a drama or a mimicry, and before that, there used to be a classical performance. The temple authorities could not take away the classical performances from their menu. And I remember my father and I enjoying these classical performances and everybody else in the audience wanted the Bhagavathar (a devoted minstrel) to shut-up and go. That is my basic education. Yes, my father has been an ear to me in that sense. Then when I came to the film school, I started listening to Ravi Shankar and other classical musicians in the listening room of the film institute. I recollect my teacher telling me to pay attention to the sound of the Veena and the Sitar. The Sitar, Santoor and Sarodh were the three instruments I had heard outside of Kerala. Maybe that was my first initiation towards classical music but I was drawn by these three instruments. Every time I heard a Sarodh I start weeping.

There are majorly two different musical traditions that I’m exposed to—the Carnatic music and the Hindustani classical. Then of course, the western classical as part of the studies that I have been to. But I feel I’m very close to Hindustani classical music because the exposition is slow. The pace is very slow, the taans are slow, it prepares you, aalap really prepares you to the dhamak. But in Carnatic exposition everything is fast, the movements are fast, the taans are fast. Probably there is more importance to the composition in Carnatic music. Whereas, in Hindustani, I feel the composition is just one thing, you as a musician how you interpret the composition is more important than the composition itself. So in that sense, Hindustani classical music allows me to be more ‘finding myself’ with the music. So I get very drawn to Hindustani classical music, though I got exposed to it very late in my life, and I had the good fortune to be able to be part of some of the greatest musical tradition in this country. If you compare a Veena (Saraswati Veena) and the way they play it in Carnatic style and in the Hindustani style (Rudra Veena in Dhrupad style) are completely different in its exposition. The Rudra Veena reminds me of the human voice, it is probably the closest to the human voice. So it’s extremely different, Southern India and Northern India is so vast and different in terms of approaching their classical art.

Then as part of my studies, I got exposed to western classical music. Then through cinema, I got exposed to all kinds of music from all over the world. Be it all the psychedelic rock, the metallic rock, all the western pop stuff, all the serious operatic music. All the experiments that happens in the western music, mainly the blues and the jazz. I have heard a lot of stuff. Though my serious listening of music was for about five years, I would say, and that is what has made me and helps me every time I work with sound. I realised that I have not learnt music, but I had some sense of music within me. I can’t read a musical composition and neither can I write them. A musician is someone who has music inside them, likewise, I also have music inside me. A musician uses a musical instrument to express himself, I use microphones to express myself in the same way. For a musician or for a Veena player, the Veena is his instrument, as a sound man, I’d say microphones are my instruments. I do not call myself a ‘sound engineer’, well maybe when you understand my work, you should understand my work as ‘engineering’ in a higher sense of the term and not just as a person who is operating equipment. I’m more of a sound designer. I try to tell stories with sound and for me music is just one element in that story telling. I’m creating music, I’m creating compositions, it need not necessarily be musical compositions, but I’m creating compositions with sound. Sometimes it’s musical in nature, because it is following a rhythm and a structure, and it has emotion in it. That’s what music does to you.

GD: What contributions have you made through your work?

RP: I do not know if I have made any contributions. It is other people’s perspective. I have worked very hard to make people understand what I think is good for film making. As a student, the only thing that has bothered me when I watched films from the west—which is Hollywood, European cinema, Eastern European cinema, the Russian cinema and everything that I had seen, is that their films came across to me as different. It came across to me as close to life more than the Indian films I watched. I hated all the Indian films. I realised the difference is in the way sound is done in those movies and in our movies.

I used to tell my friends that, “Either, I should have been born in the west or I should have been in my teens in the 70’s”. They used to laugh at me for thinking that when we make films, we don’t respect our actors! I think that is one of the biggest mistakes that we make. If you are not capturing the performance of an actor when he is actually acting it out, when he is in that emotional state, when he is in the right acoustic environment, we are not doing justice to film making; neither are we doing justice to the audience paying money because you are not giving their money’s worth. It’s like a singer doing a lip sync in a stage performance. It is just as bad to me. So that was my idea, to change that attitude towards film making first and foremost, so I went around, the rest of India, trying to make people understand. I thought Kamal Hassan will be one person who will do this, who will understand what I’m saying. I went to him. He was very forthcoming but to him—I was a young, enthusiastic boy, who had just finished film school, who probably did not know how film making works professionally. He asked me some of the very pertinent questions of Indian film making. He couldn’t do much to further my quest but he loved my enthusiasm.

I came to Bombay to attend my last film festival. Someone called my name at the theatre and said, “There is a shoot—can you go? The original sound recordist is not available”. I literally bought clothes from Fashion Street and went to that shoot. I did not know how to conduct myself in a shoot at that time. I was fresh out of the film school. I only knew one thing—sound and I knew what was right and what was wrong in sound. I fought with people and I got things done. I decided to never ever work in television again because it was a television work and I wanted to do only films.

I came to Bombay with the intention of going back to Kerala. I saw all my friends sitting around without a job. Then I got one more call, one more job, like that I got stuck onto Bombay. I was never planning to live in Bombay, it just happened. Bombay gave me a lot of opportunity, people were a lot more receptive to what I was saying. Fortunately, I came at a time when Indian cinema was going through a transient time. There were new film makers who were coming into the foray. They were people who studied abroad, who understood cinema, who understood what I was talking about. People were making films about the urban realities of India. I worked, in the early stages of my career, on the new Indian cinema. English speaking cinemas were being made in India. Split Wide Open, Snip, Everybody Say’s I’m Fine… They were willing to experiment with what I was telling them. Slowly, I brought the concept of Sync Sound and Sound Design into Indian cinema.

I remember there were not enough microphones at that time in India. I remember, going to a friend’s place, picking up the microphone, putting it in a bag, got into a taxi and went to a shoot—like a porter. I worked like that. I started from there. Fourteen and a half years later, when I was given the honour at the Cinema Audio Society of America, when people like Dennis Mathildon (who experimented with wireless microphone for the first time in the world), Steven Spielberg, George Lucas and all these people were sitting in that audience, Ben Burt was being given a lifetime achievement award that evening, I told them during my award acceptance speech, “None of you know me but I know each one of you because you have all been gurus to me, in a sense. I started from where there were no microphones available to me. Fourteen years of my struggle has brought me here to take this highest honour. I’m standing here today only because of one thing—the fraternity I was working with were receptive to changes. They were willing to accept challenges. They were willing to try new things. I thank them for allowing me to grow and I take this in their name and to the enthusiasm they have shown me”. And they gave me a standing ovation!

So I come from a time where less than 2% of Indian cinema was making live sound, today more than 40% of Indian cinema is doing live sound. That’s a huge change. Huge workforce has come into it. A huge enthusiasm has come into it. Other professionals and audiences, for that matter, have started respecting technicians, creating an awareness. I only did my work but along with my work, people got aware of what I was doing. I don’t know if you can call that as a contribution.

The other thing that I had in my mind, when I was a student, we were never allowed to source sound from libraries. We could hear them but we were never allowed to pick up sound from the libraries. The institute and its faculty believed that every film need its own sound. So we had to go out and record for every diploma film we had to make. The institute had a huge library. Then I realised that there is no library for Indian sounds. That is my second passion to create a library for Indian sounds.

So 1995 – 97, two years, I have proposed to people and started recording. This library would allow people to source sound, until then, there were no codified library of Indian sounds. For example, if you want to use some sound in a film or a television or in dramatic exposition, you can source sound. You can source a city sound or a cityscape or you can source a car sound, anything you can use from the library of sounds. Nothing of this sort was available on Indian sounds at that time. You can’t use a London city ambience to Bombay and I had realised that Indian soundscape is peculiar. People had personal collections which they have recorded themselves. Nothing was commercially available that people could buy and use. In 1997, stereo microphoning and its technology was just being introduced. So I managed to procure some stereo microphones. Humongously expensive, even now, I would say. So I got Schoeps MS microphone system to record these sounds.

I created this library of sounds. It’s called—Essential Indian Sound Effects. I have released three CDs. Then I stopped it because I was very disheartened by the attitude of people. Because for them it was an easy way. I started hearing my sounds in every Indian cinema. Every Hindi cinema had my sounds. Every Indian commercial had my sounds. It disappointed me because I thought I was making people lazy. Then I stopped. Now I share my library with people in exchange of theirs. I still have a huge collection of Indian sounds.

GD: Could you recollect the first time you heard something that captured your imagination as a kid?

RP: There are a lot of instances like that. We had lot of cattle, chicken, goats… at the backyard of our house in Kerala. Our day revolved around the Sun. The moment the Sun is up, all the living beings were up, so were we. Our life moved around that. There is one very particular sound that I remember. It was a time when rubber plantation had started in Kerala and there was a neighbour of mine, a young chap maybe in his 30s at that time, was a rubber plantation tapper. He collected rubber sap for a living. He started his work very early in the morning. He used to walk to the plantation and he used to carry a live radio with him every morning. The land around my house had a semi-circular road, adjacent to it, and this neighbour lived on the other end of this road. So I heard, for the first time in my life, sound is moving from one corner of my house to the other and it was beyond me. This radio reading out early morning news, Akashvani tunes and it used to move around me.

The other sound I remember is that of the blacksmith, there used to be one living behind our house. The sound of the blazing fire, the hammering of the metals and his grunts. More than the hammer I could hear his grunts. There were a lot of domestic animals I lived with. The forest was nearby. At night, our animals were taken away by predators. In the middle of the night suddenly you hear the sound of the hooves of cattle and then a grunt… then all goes silent, may be one amongst them was gone! My mother would say “do not go out”, I remember lying in the bed, listening to that deaf silence, anxious to know what happened, worrying whether my little goat is gone or not!

A sound always stayed with me because it gave me an emotion. If there is something that stays with you it is because it has created an image in you. That’s what I do. In every sound that I hear I look for an image and if there is an image then it stays with people.

GD: What more do you plan to achieve with Canaries Post Sound?

RP: I want to start my own music label. I’m not finding time for myself. Every film that comes to us is a challenging one, one way or the other. We have just finished a film that is an underwater 3D film. I’m just toying with the idea of 3D sound in cinemas. So every film is a challenging proposition for sound. It just attracts me, it takes away from me the other things that I’m planning. The things that I had planned eight years ago, I’ve not been able to execute it, which is having a portal for people to download Indian sounds from my portal and the music label.

There is a disappointing trend in the music scenario today. What is music industry in India? Everything is supplied by Bollywood. The music industry in India is mainly song recording, I’m assuming 95% of it or let’s say 80% of it with about 10% classical, 02% bhajans, 02% albums and all of that. If you put together, 80 – 85% of music production in this country is Bollywood songs and dances. With the advent of digital technology, it’s a sorry state of affairs, we care a damn about recording! The industry doesn’t care about recording because everyone has their own home setups. There is Pro Tools or Logic, they connect to any microphones, and they don’t even think what a recording chain is all about. They don’t think that they need a good pre-amplifier or a good I/O. The higher quality that we had achieved in the analogue era is completely lost.

As a sound designer, I get music tracks which are redundant, which by no standards can be called professional. Most of the times, I’m mixing music where I’m trying to save it sonically. Music is not a separate entity in films, it has to be part of the sonic spectrum of the other sounds in the film. So I’m trying to find a balance, I’m trying to educate people. Pure recording has been lost out which is the biggest tragedy of digital era, at least in India. The biggest tragedy of digital revolution in India, in the music production stage, is that we have either completely forgotten or least interested in doing good quality recording. There is a beauty to it. People are not understanding what microphoning is. I’m a person who cares about how microphones hear sound differently. One single sound event and ten different microphones would hear it in ten different ways. If Indian classical exposition is about finding microtonal ornamentation between two notes, as a person coming from the tradition, as a sound man, I’m trying to find where one microphone is meeting the other microphone.

Sometimes I call my art—“Recording Art”. Nobody seems to care a damn anymore! Also, what goes in the recording chain: it’s the microphone, the pre-amplifier, it’s the I/O, Pro Tools or Logic or anything, the software does not matter; what we feed the software and how we feed it is what matters. I have not come across a single recording, in the last ten years, that doesn’t have higher harmonic distortion. People are not hearing higher harmonic distortion in their recordings. Pure recording, in a way, is history now.

My idea with creating a music label is to do pure recordings. I want to do justice to a musician. I want the microphones to hear the way I’m hearing and give that to the audience and listeners. I want to record events that need not necessarily be part of the main stream business plans. I want to go down and record the sound of a Mizhavu (a big copper drum played as an accompanying percussion instrument in the Koodiyattam and Koothu, performing arts of Kerala) and give it to people. I want to record the rendition of Dhrupad (the oldest surviving form of Indian Classical music and traces its origin to the chanting of vedic hymns and mantras) of my friends in Bhopal and I want to give it to people. That is what my music label would do—offer pure recordings.

GD: Where do you master your recordings?

RP: I’m not a music person, I’m a film sound man. I don’t do anything else. I master my own tracks. In terms of film mastering there is Dolby involved, so Dolby does the mastering of our mixed track. It happens in Dolby certified studios meant for cinemas. So we don’t go out for mastering elsewhere.

The concept of mastering sounds quiet weird to me, especially the way it is done in the music industry. They do a mix and send the mix for mastering. What does the guys in the mastering stage do? They would do more compression, they would do more EQs and what else? Why don’t we do that in the mix itself? Pass it through some Vacuum Tube stuff and amplifiers—so that it changes the colour of the original sound? Is that what you intend? You are actually giving out stuff that is not yours as it is not what you imagined.

I have a complete distaste towards the whole concept of mastering in the Indian music industry. You do your mix properly and that’s what A. R. Rahman does. He listens in a way his audience is listening. He understands what the audience is listening and he incorporates that in his scoring. We lack that understanding.

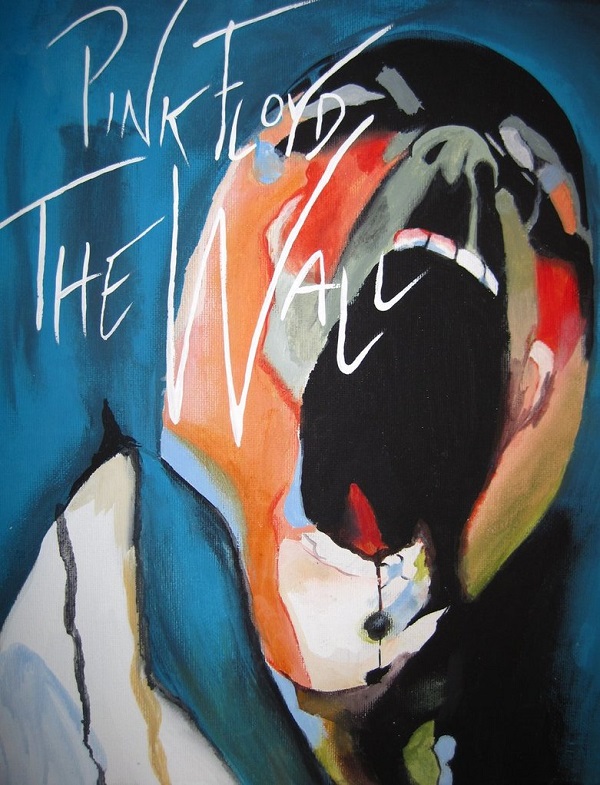

GD: Why does older recordings from artists such as Pink Floyd and Dire Straits sound so much more dynamic?

RP: Pink Floyd and Dire Straits are not today’s artists. They were from 30 years ago, so let’s not discuss them. We can’t even reach up to them. Period. And why? It refers to something that I said in the very beginning of this interview—“They were creating images”. Pink Floyd is my favourite band, because they are the ones who made me listen to sound images when I was studying at the film school. You listen to the man shouting in the album—The Wall, you know that man is standing down there! You hear the lady walking up to you. Whereever you are in the world, you hear a room, you hear a perspective, you hear images and what we are losing out in today’s mixed tracks are images.

Currently, every album, music and soundtrack is prone to loudness war in some way. I’m fighting that because whatever we are talking today are our concerns. This is not the concern of the business. So as a professional, I have to balance my aesthetics and concerns with the business that I’m involved with or else I’ll lose out. I try to be sensible within that war. I try not to hurt my audience within that war. I try not to put in more harmonic distortion.

I’m actually not in music business, I’m in the business of cinema. I’m telling stories with sound and I’m far better off compared to others in the music industry. I have one and a half or two hours of time with my audience. It’s like someone (audience) is on an appointment with me and I ensure that I’m working with a concept. I would be bombarding him, but not all through the film, at points—I would make him get up from the seat, I would make him cry, I would make him laugh, I would make him go through every emotion that sound can give him. I do that very intelligently. I’m far better in this loudness war than compared to others in the music industry that you are referring to. I only do mixes for films. The CDs and the two track album mixes and their mastering is not under me.

GD: How many movies have you done thus far?

RP: I have done more than 60 – 70 films. India’s official entry at the Oscars this year is my film – The Good Road.

GD: Do you experiment with sound?

RP: Yes I do experiment with sound and that’s all I do! I’m in the likes of Randy Thom, Ben Burt, Richard King… those kind of people. Randy Thom and Ben Burt are like my buddies. I love them and I keep their work very close to me and they have taught me, invisibly, how to create images in cinema. I’m also doing work of sound outside cinema, like Sound Art. My work “Songs Of An Island” along with visual artist Kabir Mohanty has been shown in many art galleries across the world. I’m doing a light and sound show now about the history of Andaman Island, where I’m taking Dolby Atmos technology in an outdoor space. In my sound designs for films I try and incorporate varied streams of sound work, may be in one scene or in one shot, but I try and do it. It’s like saying; I search for “silence” in each and every one of my films, sometimes I don’t find a space for it but I do try!

GD: How has life changed after winning the Academy Award?

RP: The fact that you, and more people like you, hunt me and you have come down here to talk to me is a change. I have not changed. In fact, it has only made my life hell a little bit though. People are scared to come to me. They think that I have an Oscar so I’m somebody who will judge their work, stoop on them and that I’m expensive etc. I have lost a lot of work because of the Oscar. I’m going to complain to the Academy and that they have to give me some stipend. There is a weightage that comes with it and it’s very heavy.

Now, every time I get a film, I work harder because people have started expecting some things from me. I have to surprise myself extraordinarily to impress people or for people to say something nice about my work. It’s a huge responsibility. I conduct myself well enough, there is always shortage of time and money when it comes to film sound. I actually put my heart and soul in every film that I do and it has not changed. An Oscar can’t change that!

GD: What equipment do you use in your studio?

RP: There are only so many number of microphones, number of gears… etc. that is available. I don’t think they matter to me anymore. What matters to me is how I use them. The very same gear used by my colleagues does not sound the same as when I use them.

When I was doing the film Ghajini, I was using two Portadrive (a hard disc based recorder) because eight tracks was not enough for me. When I was working with two tracks Nagra or DAT, two tracks was not enough for me so I found this weird way of locking time code—taking the time code of one machine and locking it to the other and recording in four tracks on locations. I was one of the first to ever do it. Then the Portadrive came in with eight tracks. I was happy even though I felt limited. I coupled two Portadrive and I coupled many recorders in Slumdog Millionaire because the tracks count went up to more than 20 at times. I feel we should not be limited to the number of tracks that are available.

I miss Cooper Sound, it is one of the best audio mixers that can be used on location. I have a custom made Cooper Sound audio mixer with me and I’m still managing with that. There is a new manufacturer who came up to me and asked me for my specific requirements, and we are in the process of putting up something together. The requirement has gone up so much in film production, yet it has to be compact and ready to go.

The recent film that I had done—Highway, it’s all on a truck. I’m in love with an ENG audio board called SQN which is made in England. I asked SQN to make something new for me. I just told them my requirements. They were very open to it and they increased the number of channels etc. It was of tremendous help to me. I’m looking for things like that—production mixing solutions.

I have a few sets of microphones. Some are my favourites. I use Neumann microphones a lot. I also use Shoeps. The radio microphones that I fell in love with is from Audio Limited. Those are my favourites, it uses a lot of tops with it. I also use Blue Bottle microphones. My stereo microphones are by Sennheiser. I also have a 7.1 microphone by Holophone, it’s a new technology. I also use Beyerdynamic and Sanken microphones.

For speakers, I use Blue Sky. I did a lot of research and a lot of listening tests, because what we need in a film production is something that playback faithfully. A speaker that is true to sound effects, music, dialogue and everything else. Mostly the cinema speakers are JBLs. Now the Martin Audio and Mayer Sounds are coming in. They are all far superior speakers.

In a small room such as this (RP’s office at the Canaries Post Sound) which is a replica of a theatre, it is following a ratio and a specific structure where we do multi-channel designing. When we do all that, the low frequencies become a huge issue. So I find Blue Sky’s bass management system far superior. So I actually hunted for it, got it down from Los Angeles (LA). Then they came to know about it and I wrote about it on my website. When I was in LA they came and met me. They were very happy to see me and today—they are willing to do anything for me. So I use Blue Sky and that has sort of become an industry standard.

In our dubbing room there is Dynaudio. One mixing room, down the road, has Dynaudio. All the music rooms use Dynaudio. That’s not our cup of tea. We need something much harder. Genelec is very sweet and warm. Not our cup of tea either. I find Blue Sky a mixture of Dynaudio and Genelec. So I have the low end and the high frequencies.

I have a few custom designed headphones. Over the years, my headphone preferences have changed. I used to use a Beyerdynamic DT100 and 150 when I was a student. Then I used an AKG, I forgot the model, I used it very briefly. Beyerdynamic DT100 was the industry standard, sort off, mostly used for film work. Then I started using the Sony MDR 7506, they are professional headphones, but it did not sort of please me. Because when we are recording on location, we are more concerned about the kind of rumble that comes through. Lot of rumble, lot of hums, I wanted to hear more of them.

I then moved on to Sony MDR 7509, but I did not like their build quality. Now I use the Sony MDR 7509 capsules with a very strong, specifically custom designed frame. It’s basically the same thing that a pilot uses in the aircraft. It’s designed by Remote Audio—a couple of friends in LA suggested me to try them.

GD: Why does some studio headphones sound clinical?

RP: We want to hear every unwanted sounds in our recording. In our basic work scenario, we always have a generator parked nearby, 100 – 300 meters away. You also have vanity vans, so we constantly dealing with low range hum. Then we have the earth loop, we also have higher harmonic hums that the lights are creating. Then there are a lot of RF interferences. We need to hear them all to judge whether this is within the range that we can deal with or not. I basically don’t do any roll-off on location. I keep them, record them flat so that we can decide upon them later. Sometimes, in cinema, it’s strange and different, something that you think is noise is actually not noise—it is a sound that can create a tension, every sound that you hear is usable. It’s very premature to make these decisions on location.

Recently, I did a film with Harvey Keitel, I recorded the whole film in 96kHz and the entire post sound was also in 96K. The ambience that I would have considered as noise in 48kHz is no more noise, it’s a beautiful sound and I used them. So our concerns are different from an audiophile. I’m a film sound person, every sound has a function in a story. Audiophiles, musicians and my concerns are quite different. For me—“Everything in a recording is usable sound”.

GD: Do you pay attention to power supply and cables that you use? Do they make any difference?

RP: On locations we are basically running on batteries. We never ever rely on AC power. Here, in my office, except for speakers, everything else is on UPS.

I use Gotham cables with Neutrik connectors. That’s also the cables that we use with microphones. They are expensive cables. Yes, cables do make a huge difference! I have cables that are specifically shielded when we are exposed to high frequency lighting conditions.

The audiophile brands that you talk about are not for the film guys.

GD: Do you prefer solid state over vacuum tube equipment?

RP: I’m not averse to it at all. I have heard some of the best Indian classical music in a tube recorder. Probably, I’m the only guy who has done digital restoration of 70 years old recordings. I had come across some recordings that were done in the palace of Udaipur. Those were recordings done on a tube equipment—quarter track recorder. I have digitally restored those tapes and then we came out with a series of albums called—“Heritage Recordings of Mewar Court”. I’m pretty aware of what tube equipment can offer. Because what I heard in that system, I have not heard anywhere else. I loved what I heard!

The most modern theory is actually referring to what is an old one, like the way quantum mechanics is going back to Newton’s photon theory. The most modern digital technology is actually trying to emulate the tube recordings.

GD: What music do you listen to?

RP: I listen to Classical music—mostly Hindustani. These days a lot of work that people send me. And a lot of radio too, a lot of it is decayed stuff but that makes me aware of what’s happening around me.

Pink Floyd is one of my most favourite bands and The Wall is my favourite album. And the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band is another favourite album.

I mostly listen to other people’s work. I listen to John Williams, I listen to Thomas Newman, Hans Zimmer, A. R. Rahman… Those are the work that I look up to. But I’m open to all kinds of music and sounds.

GD: What do you think about free downloads and piracy?

RP: There are two ways you can look at it: one from a business point of view and the other from an artistic point of view. The same thing happened with my work—Indian Sounds, when people started using it, I did not object to it. As an artist, everyone wants their work to be heard, seen and enjoyed. So in that sense, I don’t have any problems with people copying my stuff or using it. But at the same time, I want people to respect an artist’s work. There is a certain hard work that is gone into it. Somebody’s life depends on it. So I also feel it is very imperative that there is certain economics involved in it. And if you want to value someone’s work then you have to give something back to it. In that respect, I don’t enjoy pirated stuff.

GD: Do you have any other hobbies?

RP: Playing chess. I don’t want to sound like a brainy!

GD: Who has been your greatest inspiration and why?

RP: There are many people. There are a lot of writers, lot of philosophers, thinkers, film makers… who are my inspiration. There is Nitzsche, there is Osho, there is Foucault… then there are filmmakers like Tarkovsky, Bresson, Ritwik Ghatak

When I was in eight standard, I was in love with detective novels, so I wanted to be an IPS officer, then I wanted to be a doctor, then I wanted to be a physicist. When I was in school, I wanted to be like Abraham Lincoln, then I wanted to be Karl Marx, Gandhi Ji, then I wanted to be somebody in some stage or the other. So it keeps changing. I love the fact that I’m not fixed on one idea.

GD: What is your most memorable moment?

RP: Winning the Oscar!

GD: What is your favourite quote?

RP: I have to look into my laptop (and he laughs)!

My favourite quote and motto is: “I shall pass through this world but once. Any good, therefore, that I can do or any kindness I can show to any human being, let me do it now for I shall not pass this way again”.

For more information on Canaries Post Sound please click on this—LINK.